By Tim Dewar

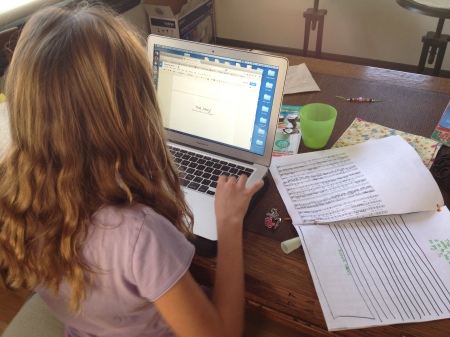

My older daughter has written her first five-paragraph essay for school. In the language of the Common Core, and since she is in fourth grade, it was an opinion piece. The topic? Should students have more or less homework? She argued for less with a tone best described as “Duh” by a colleague who read the final version. My wife and I kept our hands off of her drafts, letting her teacher dictate the process, classmates provide response, and the red and green squiggles of Google Docs do the editing.

The assignment, taking just over a week, was not particularly painful for her. She likes to write, often purchasing notebooks as souvenirs when turned loose in a gift shop. She once told me her best subjects in school were “writing, reading, and paying attention. I know ‘paying attention’ isn’t a subject, but if it were I would get an A in it.” And apparently she had paid attention to the classroom teaching. Her paper earned her a “16/12.” Above scale, off the chart.

Living in Words

So why am I not thrilled? Because I know what is coming. Umpteen more versions of the same paper. For the next 8 ½ years. The topics will change (Four-day school week? Paper or plastic? School uniforms?), but I fear the process will change only in one significant way – her reaction. This opinion piece demonstrated not only her achievement in a new form, but also the joy she finds in writing. Her fluency as a writer comes, I think, from lots of reading and her comfort with using language to do tasks she sets for herself. She has seen lots of authors do lots of neat things with words. They have made her laugh and cry, giggle and gasp, and have transported her to distant times and places, including far past her bedtime. And she wants to do those things, too, with postcards to friends, notes to her sister (and less often, her parents), stories starring her toys, dolls, and lovey friends, further adventures for book characters (fan fiction!). The same week she wrote her opinion piece for school, she produced a nine-page magazine, News For Everyone, with craft ideas, poetry writing suggestions, a short story, a non-fiction informational piece, and an advertisement for a local play.

See, it is not just reading that has kept her up too late. She is just as likely to choose to write before going to bed as to read. Those notebooks from the gift shops? Filled. Some started off as diaries, later to become illustrated adventures. Others are pages of lists, including favorite words. Still others are filled with secrets that must be hidden from parents’ eyes (and sister’s, too!). There are many pages of starts and beginnings, wild middles, that then run out of steam. Loose-leaf notebook paper gets tied with yarn to make “books.” This is a child who lives in words, her own and those of authors.

As she explores this world of words, she takes risks, seeks new pleasures, revisits familiar favorites. But all the time she is setting the course. What makes her a strong writer is not her mastery of the five-paragraph structure, but her interest and courage to try to do new things with writing. I worry that the string of poorly conceived opinion, and later, argument essays that my daughter (and her classmates) will likely be assigned will diminish the interest and eliminate the courage. I fear that when we do this, we not only do not help non-writers become writers, but we teach those students already in love with writing that we must not know the first thing about writing or writers. How can we if we are just teaching forms? Or worse, we teach them that writing isn’t about the joy and struggle of finding what one has to say. Instead, writing is some kind of game with the teacher as rule-maker and opponent. Writing will become this rote filling of a template that someone else devised. It will become work, rather than play, a drudgery of finding evidence and inserting transitional phrases in the right places.

Five Paragraphs and Three Types

The five-paragraph theme structure is often advocated as a scaffold for writers, something that supports beginners until they are ready for more sophisticated forms – See, for example, here and here . English Journal published a spirited defense, written in five paragraphs no less, from Kerri Smith. Forty years prior Duane C. Nichols articulated the form’s features in the same professional journal. These on-going professional discussions about when and how to introduce, then wean, students from relying on this formula assume that writing is the acquisition and mastery of forms. If this were true, couldn’t my daughter with her “16/12” be certified as having mastered the five-paragraph essay? She could get a card for her wallet or a badge from Google Drive or something so that the next time a teacher asked for her to express her thinking in an-intro-three-body-paragraphs-and-a-conclusion, she could just flash her badge and say, “Sorry, I’ve got better writing to do.”

Our challenge is to teach our student writers that writing is this amazingly powerful tool for shaping the self and the world. While this has never been easy, the current educational landscape makes it more difficult. The Common Core standards are often unfortunately, and incorrectly, understood to define writing as three “types” – argument, informational or narrative (see Writing Standard 10, Appendix A, and Arthur Applebee’s “Common Core State Standards: The Promise and the Peril in a National Palimpsest”.

College, career, and life readiness requires much more than knowing prescriptive forms for each. I want my writers to be able to recognize a situation that requires writing, have a variety of processes and tools at the ready, and the courage to write. With that, writers can change the world.

Tim Dewar, Ph.D., is the Director of the South Coast Writing Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he teaches undergrads, credential candidates, and grad students, drawing on his experience as a secondary English language arts teacher, research, and, most importantly, the expertise of writing project teachers.

Pingback: “I’ve Got Better Writing to Do.” | teaching knowledge and creativity

This sounds more like an argument for differentiating writing instruction than it does an argument against the five-paragraph essay. I made the point in my piece that this structure is one that is helpful to very low-level students as well as ones who are very task-oriented and quantity-oriented and cannot seem to handle having the freedom of figuring out their own structure for their writing.

You seem to take issue with teaching various forms of writing. I agree with you that there aren’t just three forms; however, when you look at the basics of any writing task–voice, audience, and purpose–you see that there’s a certain mathematics to it that allows these forms to be useful. Where I stand teaching high school, I work on using writing as a form of expression, whether that be creative or to demonstrate all of the buzzwordy skills we hear about (critical thinking, etc.). But many times, my students come in way below that level and it can be a juggling act to make sure everyone is being met where they are–after all, I have 100 students.

No, we shouldn’t be defaulting to processing five-paragraph essays because that would defeat the purpose of building better writers. But as I thought I had pointed out in the post that you linked to, I don’t think it’s an either/or thing here. To use a phrase that’s probably a bit cliche, don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater because this still can be useful.

Thanks for your thoughts, Tom. Differentiation would help. So would a bit of analysis of the task, including helping these young writers think about audience, purpose, genre, and voice. Analysis of a rhetorical situation and responses other writers made to similar situations seems to me a better place to start than with a predetermined form. Such an analysis might lead writers to conclude that a five-paragraph essay is the best form, though I confess I have my doubts. I think that the analysis would reveal that this writing assignment had no purpose other than to teach a form. That is when I get concerned as a writing teacher – when we just start teaching forms separated from audience, purpose, and the genres that have developed outside of school, in the wild, so to speak. I worry further when CCSS and its three “text types and purposes” are used to justify this type of teaching. We know better, and can do better.

Tom dewar2013: AM i MISSING SOMETHING IN YOUR ORIGINAL POST? WAS DYING TO READ THE ESSAY IN QUESTION, BY YOUR GIFTED AND LUCKY-TO-HAVE-YOU-AS-A-DAD DAUGHTER! Just signed up to follow your blog, as an emerita in the Bay Area Writing Project long ago invested in changing how writing was being taught — Love hearing your shorthand, take-it-for-granted description of the process her teacher supported — Yay. I will enjoy hearing your observations at this point in history — AND would love to think we might get to read the actual writing of students whose work you are citing or talking about (with permission of author, of course!) Somehow, in this instance more than any other, “showing” feels like the sine qua non for making sense of the “telling.”

look forward to reading you!

Hi Catharine,

I did not post the original essay by my daughter, partly out of concerns about her privacy, partly to keep the post brief. This also prompted the shorthand description of the writing process which you enjoyed. Brevity is soul of wit and all that. I take your point that showing more of her and other students’ writing can often make the case better than any adult’s analytical telling. I think this is the subject of a future post.

BTW, this blog (Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care) is not mine. It is the product of a group affiliated with the Conference in English Education. They are always looking for contributions. Your history with BAWP certainly provides you with material to share. See the submissions tab for more. I would love to see what you can show and tell.

Hello, Tim. I have assigned that very same essay topic to seventh graders—well, some variation of whether homework is helpful or harmful. Also, should students be allowed to chew gum? Use smart phones? The list goes on. I admit that those essays get boring.It never occurred to me that students had been writing that same essay since fourth grade. What is the solution? We know we have to teach “argument” and I suspect that many teachers, myself included, try to mimic the testing situation students will have to face in the spring. Maybe we should wean ourselves from that objective and ask students to take on all kinds of real-life argument tasks. I’m imagining book, movie, or video game reviews. Kelly Gallagher suggests that we often write to evaluate and judge and also to take a stand or propose a solution. Students can evaluate the effectiveness of television advertisements or the credibility of websites. They can propose solutions to global issues such as climate change or even personal issues like how to add exercise and healthy eating to one’s life. The problem for teachers then becomes that the more choice and freedom we give students, the harder it is to scaffold for individual students. Some students need one-on-one attention to be able to pursue individual topics successfully. That is very hard for secondary teachers with 150 or more students.

Hi Amy, I like the idea of writing real-life arguments like reviews because then we can have students read real-life reviews to see the varied organizational structures writers use to make their case for a movie or book or product. I just saw a piece about TripAdvisor in Outside Magazine. Though not the main point, the typical pattern of a review is discussed. It’s not five paragraphs.

Like Kelly Gallagher, I think problem-solution is a powerful way to frame a writing task. This allows the writer to set the terms by defining the problem.

And if you’ll allow me to challenge a point you make, I think when students have more choice, and consequently are more invested, the teaching becomes easier. The problems they face/need help with come from real writerly situations, not a disinterest in the topic or a lack of knowledge about the topic. Plus there is typically an increase in engagement from the writer. Even if all students are writing to the same topic (and the same form?!), they aren’t writing the same paper. A teacher can’t say to a class of 20 or 38, “Everybody put a transitional word in the eighth sentence.” The need to help the individual writer never goes away. Or to reframe it, helping an individual writer is the essence of what writing teachers do.

As a college professor who teaches freshman writing, I can’t agree enough with your suggestion that HS teachers stop teaching to the kind of essay students have to write on the standardized tests. I realize that puts you in an awkward position because student test performance matters to your job, but I’d suggest that HS teachers teach research skills and complex reading comprehension as fundamental components of any argument paper. Paper assignments like the ones described here set students up to think that the be all and end all of argument is “that’s just my opinion.” I’m trying to get them to understand that 1) informed opinions are more valid than uninformed ones, and 2) argument is done in conversation with ongoing discourses. If students could arrive at college familiar with the “they say, I say” model of writing in which they have to synthesize 2 or more sources on the same topic and then argue for their own position in response, then students would be much better equipped to handle college courses across the board, not just the required writing sequence. Your idea of teaching more real world arguments is excellent.

Thanks for offering your perspective from the college level. I find comfort in discovering I’m not alone in my thinking. I would take more if it weren’t for the research of George Hillocks on the influence of state-wide, standardized writing tests on writing instruction. I feel like I am watching the changes and process he objectively described in /The Testing Trap/ play out in my daughter’s school experience. She started school the year California adopted CCSS. Each year the coming newly aligned tests have played a bigger role in her education. I’m not mad at her teachers; I understand their predicament, as do you. I speak up because I care.

An Update: Yesterday I had a chance to read my daughter’s “informational piece” on solar energy. It was done as a common formative assessment in the presumed format of the SBAC exam. She read a number of non-fiction texts and watched a couple of videos, dutifully marking the text and taking notes. The final product scored at the highest level. And was five paragraphs. I think I feel another post coming.

So often school is where kids “do school.” This includes practicing writing forms that reside in very confined contexts for very specific and narrow purposes. It’s no wonder that we struggle with convincing many learners that the way we “do school” is relevant to their lives- that it matters.

Too often school becomes this endless cycle of preparing for more school. “This will be on the test.” “You’ll need to know this for college.” My colleague Linda Adler-Kassner calls this “teaching up.” Always teaching the thing that is assumed the students will need to know in the next grade or school. I wonder if this is more true in writing than other areas? Do other fields have genres (or the equivalent) that don’t exist outside of school? I would lose hope, but the SAT eventually abandoned analogies.

Pingback: Counterstories from the writing classroom: Resistance, resilience, refuge | Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care

Pingback: School Writing Vs. Authentic Writing | Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care

Pingback: Many students dislike writing in school, and it’s no wonder. Five-paragraph essay formats, predictable essay questions on books they didn’t choose to read, all written for a teacher (or faceless exam scorer) who knows more about the subject than they

Pingback: The Five-Paragraph-Theme Blues and Writing for Real | Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care

There are lots of ways you can apply your writing skills.. I’ve been looking for one for quite a long time, and found it during my maternity leave – helping students with their homework.