by Anny Fritzen Case

Teachers have long used graphic organizers and other instructional strategies designed to demystify and teach more complex literacy practices. Functioning similarly to a ladder, they are intended to help students progress step-by-step towards the learning goal until they are able to master the targeted skill or new understanding independently. Examples of graphic organizers commonly used to support writing include venn diagrams, mind maps, plot diagrams, and various types of genre-specific charts and outlines. Research supporting the use of graphic organizers suggests that, among other things, they can help students generate ideas, organize writing, and visualize conceptual relationships. Moreover, graphic organizers are easy to find and easy to use, making them a practical teaching resource. However, if used ineffectively, graphic organizers can replace rigorous thinking and/or result in misunderstanding.

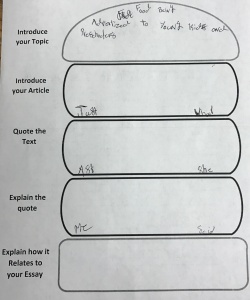

Just the other day while I was observing a 7th grade English class, I was reminded of what can go wrong with graphic organizers. In preparation for writing an argumentative essay supported by evidence from outside resources, the teacher showed students how to “sandwich” a quotation from an article. “Good writers introduce and explain their quotations,” she explained. She then projected a graphic organizer portrayed as a sandwich with each part of the sandwich representing how to frame text evidence.

Students were instructed to fill in the organizer using a quotation from an article reporting a scientific study that explored how advertisements influence children’s food choices. Ryan, a highly capable seventh-grader, had read the article and when I asked him to tell me about it, he was able to articulately summarize the main points and identify the article’s central argument. However, instead of complying with the directions on the organizer, he simply wrote, “Just ask me” and “What she said,” one word strategically placed in each portion of the sandwich. A student who had moments before demonstrated the ability to comprehend and analyze a research report shut down in the face of a well-intended instructional support. His quick dismissal of the organizer suggested that he viewed it as undesirable busywork.

While Ryan was inventing his own response to the graphic organizer, a few students completed the organizer as intended, selecting passages from the text that aligned with an argument. A number of other students dutifully followed the teacher’s directions – copying the article’s title, a short passage, and writing a brief comment or paraphrase of the quoted text. Although the organizer was designed to help students support an argument, they seemed to be randomly selecting quotes without considering a particular argument. Despite filling out the graphic organizer, they did not practice nor demonstrate understanding of how authors actually select and frame quotes within a larger argument. As illustrated from this classroom vignette, students interact with graphic organizers in a range of ways — some of which support learning and others which impede or mask it.

Similar episodes occur regularly in classrooms across grade levels when, for example, students rotely fill in bubbles on a mind map, randomly insert events into a plot diagram, or produce a formulaic essay by thoughtlessly transferring notes from a text organizer. I suspect that, in most cases, the problem doesn’t lie with the graphic organizer itself or with the students or the teacher. Rather, the critical element is how the tool is used. The following suggestions can help educators avoid the pitfalls of graphic organizers and improve the quality of thinking and writing of the students who use them.

- Be clear on the deeper purpose. Before using a graphic organizer, be sure you can articulate the specific type of thinking it is intended to support. As you are modeling use of the organizer, emphasize your thinking process. Consider showing models of completed organizers that represent a range of conceptual quality. Discuss why one model represents more rigorous thinking than another. In evaluating completed organizers, assess on content, not just completion.

- Allow flexibility. Once you are clear on the purpose, you are prepared to consider other possible representations of the desired thinking, as well as alternatives for getting there. If one type of organizer works for one student but not for another, allow and provide other options. Remember: the end goal is not the organizer, it’s the thinking.

- Use organizers backwards. When graphic organizers are utilized to support writing, students typically fill in their own ideas and from there, draft a text. Another way to help students understand a particular text or a genre is to fill in an organizer to uncover the logic of a mentor text. For example, the “quote sandwich” organizer used in Ryan’s classroom could have been used to analyze how the author of the scientific study had framed and mobilized quotations. When supported by discussion, this task invites students to consider the language, purpose, and effectiveness of an author’s use of quotes — which is the underlying purpose of the organizer.

- Remove the scaffold. In construction, scaffolding is only used when there is a need and when that need is met, the scaffolding is removed. Unfortunately, graphic organizers are too often used without a real purpose and too often stay in use after the original goal is accomplished. Back to the quote sandwich example: imagine if students were required to fill in a “quote sandwich” every time they included a quotation in their writing, even after they had mastered how to effectively frame a quote! Yet, in some classrooms, students seem to spend as much time filling in graphic organizers as they do composing texts. Time spent unnecessarily on graphic organizers is less time spent writing. What “real writers” do more than anything else is write, logging many, many hours working on a text. When we prioritize writing-strategy instruction over writing, students may well become very skillful at writing-related tasks, but are less likely to become, and to identify as, competent writers.

Photo by Clément Bucco-Lechat, commons.wikimedia.org

To sum up, when used without clarity of purpose and high expectations for quality and rigor, graphic organizers can morph into weak proxies for writing that bore and frustrate students and give rise to misunderstanding or over-simplification. When implemented productively and flexibly, they can support students’ development of higher-order thinking, effective writing processes and strategies, and high-quality texts.

Anny Fritzen Case is an assistant professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Gonzaga University where she teaches courses in secondary education, discipline specific literacy, and second language literacy. A former middle and high school ESL teacher, she enjoys spending much of her professional time and energy working alongside her students in local schools.

Peer reviewed through the Writers Who Care blind peer-review process.

Markie is your smart personal graphic designing Assistant that helps you to improve the visual aspects of your brand’s Social Media Channels by suggesting you stunning visual images for your brand.Keep sharing!!!https://www.markieapp.com/

Pingback: It’s Our Birthday! | Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care

Pingback: Reaching Complex Thinking in Argumentative Writing: The Pitfalls of Creating Prompts and Using Evidence | Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care

Pingback: When Students Need Structure: Utilizing Graphic Organizers | Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care

Pingback: Paradoxical Truth in an Orange Blossom | Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers Who Care